Government & Hospitality – Not the Best of Bedfellows

Beer and pubs are familiar and integral features of our communities and social lives. But how did the brewing and drinking landscape evolve into what we experience today? How did the laws and economics of the 1800's onwards influence the production of beer and the beloved community hubs serving it? To answer these questions, in this series for CAMRA Learn and Discover, brewer and historian Steve Dunkley takes a deep dive into the history of the brewing and pub sectors, British drinking culture and the forces that shaped them.

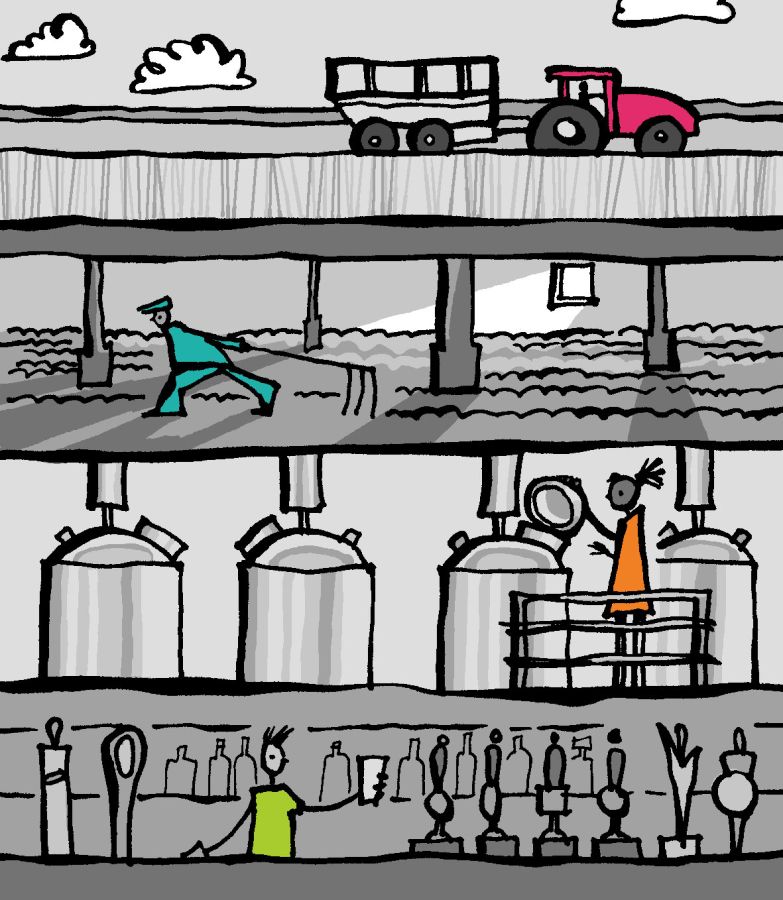

Illustrations by Christine Jopling

- Introduction

- Dark matter

- The march of the temperance movement

- Government ale

- Not strict enough

- Too much local power

- Smoke & mirrors

- Middle ground, can’t please anybody

- Walking on broken glass, cans, and plastic

-

Introduction

It’s pretty fair to say that the UK Hospitality Industry and the UK Government haven’t always seen eye to eye. The Government has generally eyed alcohol as a way to raise money through taxes, and the industry has usually seen it as a way to raise money for themselves through sales – ideally with the least taxes possible. In the end though, both see it as a way to make money. And both usually share more common goals in recent years. From promotion of a healthier attitude to alcohol through the influence of health – and religious – campaign groups, to environmental credentials; the aims of politicians and brewers have more often aligned than not. But the methods to reach those aims have rarely aligned.

-

Dark matter

In 1802 the Government introduced the ‘Duties on Beer etc Act’ which amongst putting up the taxes, introduced a form of purity law which forbade anything other than malt and hops being used as ingredients in beer. I’m guessing they didn’t consider water as an ingredient, and they treated yeast as a processing aid. Why introduce this law? Because it seems that counterfeit goods were a very serious problem at the time. Tea merchants were known for making blends from hedgerow flowers and leaves with a bit of colouring to bulk out the expensive imported tea leaves, and the government of the day didn’t trust the brewers not to do similar. This law was very welcome by the larger brewers who were very well in with the governing Tories and Whigs of the time, as it benefited them because the smaller breweries couldn’t then afford to produce the sought after darker beers.

-

This changed with the introduction of a patented process for “preparing a colour from malt” by Matthew Wood, a City of London druggist who created a dark malt extract. He just didn’t mention “beer” in his patent application anywhere as he didn’t want to tip the excise men off. So he obviously knew he was treading on legally dubious ground when he applied for it. But the patent was granted, and the smaller brewers took to it immediately.

However, in 1808 Henry Hunt of the Clifton Genuine Beer Brewery of Bristol had his barrels of malt colouring confiscated by the Excise men who deemed that it wasn’t an ingredient allowed by the law.

Hunt took umbrage at this, and through letters and runners (what we’d call couriers today) was able to get the decision quickly overturned and what he termed the “illegally removed” malt colouring returned in very short order.

From this outrage as he saw it, Henry “Orator” Hunt developed his already keen interest in politics and by 1820 had got more heavily involved, being the main speaker at what would later become known as the Peterloo Massacre; and spend some time in jail for his part.

-

The march of the temperance movement

In 1915 the government were deeply concerned that excessive drinking was taking its toll on the workforce that it needed to produce munitions for the Great War. There were a lot of reported sick days with staff not turning up for work because they were a little hungover. Which when you think that they were making bullets and shells for the war it wasn’t too bad a thing that they weren’t at work if the room was spinning for them. It was either that or potentially blowing the place up. A Liberal MP of the time, David Lloyd George was quoted as saying “We are fighting Germany, Austria and drink, and so far as I can see the greatest of these deadly foes is drink.” Which shows that he never went to the front lines while those bullets and mortars were flying.

-

To combat what they saw as a reduction in workforce efficiency, in 1916 the Government took control of alcohol production and distribution in three areas surrounding munitions factories and armouries in England and Scotland. The main area, which was also the largest and seen as the most successful intervention was between Carlisle and Gretna. To increase munitions production to the levels needed the Government created a brand-new purpose-built chemical and munitions factory so large that it required new settlements at Eastriggs and Gretna to support it. Where there were previously sleepy towns, there was now an increase of an estimated 20,000 people to both build and work in the factory. The area was remote with not much entertainment for the relatively well paid workers who were put up in cramped houses or temporary huts. So when they had some down time, they wanted to relax and enjoy a bit of luxury; which is where Carlisle came in, being the nearest city to the factory and just down the train line.

-

It wasn’t long before the streets of Carlisle saw a four-fold increase in alcohol related offences. The local population prior to the First World War was approximately 45,000 and was estimated to be closer to 20,000 by 1916 – mostly made up of older generations, women and children. This was ripe ground for the Temperance Movement to push for major changes to restrict the consumption of alcohol, and it got them. The Government took control of all breweries, distilleries, blenderies, bars and all but three hotels in the area. Only the Government could make alcohol, which it made weaker, and only the Government could sell it, except for the two expensive hotels and their private bars, the third was a Temperance Hotel without a bar.

After the First World War two of the Government controlled areas were released back to the previous owners, but Carlisle was kept under Government control. This control was constantly questioned in both the House of Commons and the House of Lords, including a report in 1927 which concluded that anti-social behaviour was under control, but also that it was very profitable for the Government; so they kept it going. It wasn’t until 1971 that it was deemed to no longer be financially viable and they relinquished control.

-

Government ale

The Carlisle Experiment wasn’t the only time that the Temperance Movement had the Government’s ear. February 1917 saw the government ban all malting of barley. The U-Boats were causing supply havoc in the Atlantic, stopping supplies coming in from America and all the grain that did get through was needed for bread. Much to the delight of the Temperance Movement who sought to capitalise on the mass slaughter by bringing in bans on alcohol to satisfy their religious beliefs. Obviously having ignored the story of the wedding at Cana when Jesus did a brief stint as a vintner.

In April 1917 this was made even worse with brewers being ordered to produce no more than one third of their 1915/1916 overall output of alcohol. Their output volumes were already down from the previous production years as a lot of their previous customers were sitting in mud-filled trenches in Europe, but this restriction was something they weren’t willing to take laying down. Breweries across the country firmly laid the responsibility where it rested by calling this enforced low strength beer “Government Ale.” It didn’t take that long before the government brought in a new law banning beer from being called Government Ale. A sign of not thinking things through to their logical conclusion.

-

Not strict enough

Perhaps the most notorious example of the Government’s unintended consequences with the beer industry is the Beer Orders.

In the 1980 there was a call for a breakup of the monopoly of the ‘Big Six’ breweries. Between them, Bass, Grand Metropolitan, Courage, Whitbread, Allied Brewers and Scottish & Newcastle owned about 45% of all the pubs in the UK. Doesn’t sound too bad, that left more than half as freehouses. But those breweries accounted for 75% of the beer supplied to pubs which meant that they also had a hefty percentage of the beer sold in those freehouses, usually through brewery loans or cheap supply deals. Consumers at the time kept calling on the government to look into this ‘stranglehold’ of the market, especially as the price of beer was rising faster than inflation and the breweries were seen to be making huge profits. The fledgling consumer group the Campaign for Real Ale got involved and eventually the government acted with “The Supply of Beer (Tied Estate) Order 1989” that forced the breweries to limit their tied estates to 2,000 pubs, and to allow their tenants to stock a guest beer.

At the time this seemed like a huge win for consumers, more pubs would be free of tie, even more would be stocking guest ales, and with the extra competition the price of a pint would come back down.

Unfortunately, it seemed that no-one really thought this through.

-

It was only breweries that were restricted by the number of pubs that they could own, and new pub owning companies sprung up to snap up all these cheap pubs coming to market. The PubCos were born.

With no restrictions on the number of pubs they could own, or who they had to buy their beer from, they were immediately at a distinct advantage over the Big Six. The Beer Orders were repealed in 2003 but the damage was already done. By 2004 the two largest PubCos of Ei Group and Punch Taverns owned more pubs between them than the Big Six had collectively owned, and had exclusive supply deals with multinational drinks corporations, exactly the opposite of what was originally intended.

-

Too much local power

The wonderfully titled “Deregulation and Contracting Out Act” of 1994 made provisions for a new Children’s Certificate that would allow pubs to admit children for the first time. It was previously argued that exposing children to drunken behaviour and foul language would lead them to mimic the same. To qualify for these certificates pubs would have to fulfil a set of criteria determined by the local magistrates. The Act itself only stipulated that the area had a bar that served soft drinks and food, but also said that “the area to which the application relates constitutes an environment in which it is suitable for persons under fourteen to be present” and it was the local licensing authorities who decided what constituted a suitable environment and added extra conditions ranging from separate rooms to no fruit machines or loud music, and no smoking (this was before the smoking ban) or adequate ventilation.

A lot of pubs looked at the potential new family trade and installed expensive air ventilation systems. 12 years later smoking was completely banned in pubs.

-

Smoke & mirrors

Apart from a few diehards it’s generally accepted that the smoking ban in pubs was ‘A Good Thing’, it’s certainly cut down on the amount of washing liquid and shampoo needed to feel clean the next day, and the nightmare of having to clean ashtrays that drinkers have put their ice cubes into is starting to recede. Slowly.

A few venues were able to find loopholes to the outright ban. One notable pub turned itself into an immersive theatre that constantly reran a show entitled “The English Pub Before The Smoking Ban”, and because smoking was still allowed on stage in theatres as part of plays, customers were allowed to smoke on the stage of the public bar. Another niche change was a local of one small pub revealed himself to be the crown prince of a small island principality and had the pub turned into his foreign embassy, purely so the smoking ban didn’t apply and he could continue to smoke with his pints. Oh, and the “Smoking Room” bar at the House of Commons reverts to being a Private Members Club from 6pm each day so smoking is still allowed in the bar of the law makers.

-

But for the majority of drinkers smoking was banned overnight, and overnight we saw pubs empty as non-smokers were able to sit where they like, as long as they didn’t mind watching the drinks of the hordes of smokers huddled outside for their nicotine fix.

It had been suggested at the time that rather than an outright ban, it should have been brought in gradually. That any pub allowing in children or serving food should not be allowed to have smoking inside, but for other pubs it should have been the landlords’ decision. The counter argument was that the staff at the pubs were not able to choose whether they inhaled second hand smoke. This counter argument was obviously made by someone who had never run a pub and didn’t know how high the turnover of staff is. Within a year, maybe two at the most, the non-smoking staff would be in non-smoking pubs, and the smoking staff would have been working in smoking pubs. Market forces would have shown which was more successful, but the government decreed and hospitality saw several years of vastly reduced trade.

-

Middle ground, can’t please anybody

There is, arguably of course, one instance in the history of hospitality and government where they have been able to work together for a successful outcome, one which neither are happy with but both are happy to put up with. The Portman Group.

The Portman Group was founded in 1989 as a self-regulatory alternative to government regulation. A sort of “we promise to be nice if you don’t force us to be nice” agreement by the larger players in the drinks industry. Which was then sorely tested in the mid-90’s with the introduction and open armed welcome of alcopops - and binge drinking.

But the Portman Group prevailed, and eventually became more than just a multinational brewers funded tool to punish smaller producers while turning a blind eye to their own behaviour, and today is respected, grudgingly, by both sides. It’s occasionally referred to as the ASA of Alcohol, but more commonly referred to as “A bunch of interfering pricks who’ll be first against the wall when the revolution comes.” But with only a few exceptions, their rulings over the last few years have been demonstrably just and are respected by the brewing and distilling industry they regulate.

There will always be some people who push against the Code of Conduct, but these people are why we need “No Smoking” signs at petrol stations.

-

Walking on broken glass, cans, and plastic

When the ban on non-approved ingredients in beer was brought in in 1802 the government were inventing a problem to solve, and only listened to the larger, richer and donating members of the industry. When they looked to reduce alcohol consumption in 1917 to keep a workforce focussed, they only listened to those opposed to alcohol in any form, and then kept the restrictions going while they were making the government money. When they looked to open up competition in 1989 they didn’t listen to the industry itself. When they looked to improve the health of drinkers and workers with the smoking ban in 2007, they didn’t think that some workers might also be smokers or take seriously the immediate effect of the ban. When they stepped back from defining the legislation themselves; it seemed to (eventually) work.

No one thing that affects the hospitality industry can be looked at and dealt with on its own. There are multiple layers to the supply chain, from the farmers growing the ingredients, those processing the ingredients, those making the drinks and those serving them, as well as all the support and supplies that those layers all need. And those that ship everything about between them.

-

Just one of the problems with the abandoned Scottish Deposit Return Scheme was that it included glass; because glass needed to be recycled and drinks come in glass bottles.

The current kerbside collections in place meant that an estimated 63% of all glass bottles in Scotland were collected and recycled. The new scheme wanted to increase this to 90% of the 560 million glass bottles used each year; so glass was included in the proposed scheme.

The problem though was that this laudable aim was looked at just on its own, without taking into context the collection methods and haulage used and the future use of the glass. British Glass have done some very interesting work in this area and found that for every tonne of glass recycled for bottles there is a CO2 offset of 314kg. So the current collection and recycling methods offset 38,831 tonnes of CO2. But the proposed method of collection under the DRS scheme would have meant that the glass would only be suitable for recycling into aggregates and whilst that gets waste glass off the streets it actually costs 2kg of CO2 per tonne, meaning that instead of saving 38,831 tonnes of CO2 the scheme would have cost 353 tonnes of CO2. Just that one aspect would have meant an overall additional cost of 39,184 tonnes of CO2. And it wasn’t the people in government responsible for the scheme that worked this out, but someone from the hospitality industry looking into how it would impact their work.

-

The scheme was eventually abandoned at great cost after contracts had been signed, payments made and equipment bought. But it hasn’t ended there as a new scheme is being proposed that might be even worse, but might also be better.

As with the previous examples of the government and hospitality not seeing eye to eye, it really shows that we need to work together for the solutions. The government can’t just listen to a few people or companies, but must listen to a much wider range of experience and specialist knowledge, and then make informed decisions.