American Heirloom Cider Apples Part Three

Series: American Heirloom ApplesIllustrations by Christine Jopling

Things you will learn

- Cider-making regions

- Upstate New York: Fingers Lake and the Hudson Valley

- Virginia

- New England

- Craft cideries

- Future of heirloom apples

-

Hello again ciderists, and thank you for joining me for the third and final part of this series on American heirloom cider apples. Having covered both the historical and contemporary contexts of how heirloom cider apples came to America, propagated vanished and are in the process of a revival, Part Three will introduce the apples themselves. This article will explore some key heirloom cider apples by region, delving into their stories – both past and present, and will finish with some key US cider events and a further reading list. There are thousands of heirloom varieties flourishing across the US, but this piece will focus on a select few which are playing a significant role in the contemporary American craft cider movement or have especially intriguing backgrounds – both proven and apocryphal. Expect drama, controversy, surprise and occasionally disappointment. With characteristics as distinct and unique as humans, it’s easy to see how these specialty fruits have their own world of devotees.

This piece will also explore the ciders being made with these apples, what makes them special and inspiring to cidermakers, and how their renaissance is fueling a sophistication that, while niche, is elevating the standard of American craft cider, offering exciting drinking opportunities for the curious and building an engaged, flavour-conscious community among those in the know. It is local heirloom cider apples that differentiate American craft cider and make it truly American.

-

Cider-making regions

Heirloom cider apples can be found across the US. Their ability to evolve and survive to fit whatever climate they may find themselves in means that somewhere in any given region, an apple tree will be lurking. However, some regions have more friendly growing conditions than others, as well as more established histories of both commercial and heirloom apple orchards, resulting in greater means and opportunity for heirloom survival and propagation. While the North unsurprisingly dominates, there is also a strong history of apples in the Southern US. Key growing areas include the upstate New York/Fingers Lake region, New England, the Pacific Northwest and Virginia. Other regions where significant cultivation is taking place include Colorado, California, parts of the South including Georgia and the Carolinas, and the Midwest, including Iowa.

Some of the most well-known and fabled heirloom cider apples hail from these regions, and new varieties are continually being discovered and catalogued.

-

Upstate New York: Fingers Lake and the Hudson Valley

Possibly the most famous and prolific cidermaking region in the US, the fertile plains of upstate New York are kept hydrated by the stunningly picturesque spread of long, slim lakes running between the verdant, rolling hills decorated with Dutch barns and graced with perfect orchard-growing terroir. The home to many varieties of heirloom cider apples and American crab apples, the majority of the area’s farms now focus on commercial dessert apples, primarily destined for the supermarket or the huge Mott’s apple sauce production facility in nearby Williamson. Despite their long period in the wilderness, heirloom cider apples are slowly finding their feet again in the region. A trip around a few stops on the Fingers Lake Cider Trail offers the opportunity to indulge in these flavoursome delights, often freshly picked onsite, with long and evolving histories.

-

Of all the upstate New York apples, Northern Spy is among the most famous, and with one of the most hotly debated histories. Most craft cideries will offer up a Northern Spy-forward varietal, its aromatic, robust, sweet-tart lemon-pear notes making it a popular choice for both blends and single varietals. Northern Spy’s origins date right back to the earliest wave of Puritans to arrive in Massachusetts Bay in the 1630s, and the family of one Deacon Samuel Chapin. A fascinating figure in American history whose descendants would include Revolutionary War hero General Israel Chapin, Presidents Grover Cleveland and William Taft, abolitionists John Brown and Harriet Beecher Stowe, poet T.S. Elliot and musicians Harry Chapin and Mary Chapin Carpenter, the Deacon’s legacy also stretches to the Northern Spy. When the aforementioned General Israel Chapin purchased land from the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, brothers Heman and Oliver Chapin followed with seeds of the Northern Spy’s ancestor at the turn of the 19th century.

-

While this may not sound like a big deal, the town of East Bloomfield in New York’s Ontario County takes their status as home of this revered apple very seriously – so much so that a misstep in an issue of Martha Stewart’s Living magazine led to a local furor. The East Bloomfield Historical Society filed a complaint and demanded a retraction for Stewart’s assertion that the apple originated in Connecticut, which is in fact the home of the seed rather than the apple. In fact, East Bloomfieldians are so proud of their Northern Spy they have a bronze plaque to mark the spot of its first planting. Heirloom apple history is a serious business.

-

And controversy over the Northern Spy does not end there. The apple’s unusual name has sprouted myths of its own. Long up for debate, one Conrad D. Gemmer claimed discovery in a 1996 issue of the Journal of North American Fruit Explorers, positing evidence from an 1853 fruit grower’s magazine that the apple was named for anti-slavery Antebellum dime-store novel The Northern Spy by J. Thomas Warren, tying the apple’s name to East Bloomfield’s status as an Underground Railroad hub. However, as Darlene Hayes notes, the apple far predates a novel referring to the Confederate States, who did not secede until 1861. Hayes points instead to a potential link to James Fennimore Cooper’s 1821 novel The Spy: A Tale of the Neutral Ground, detailing a Revolutionary War spy’s exploits against the British. Cooper’s friendship with spymaster John Jay, a colleague of General Israel Chapin, gives this story greater veracity. Of course, it is unlikely we will ever know for certain, but such controversy around a single apple variety that survived a rabbit attack through sheer luck exemplifies the curiosity and possessiveness American heirloom cider apples inspire.

If you’re not Northern Spied out, a final interesting anecdote brings us closer to modern times. In 1953, the Toronto Globe & Mail sent a box to Senator Joseph McCarthy – the pun is in the name of course. While McCarthyism can in no way be described as a joke, this light-hearted prank actually cracked a rare smile from the infamous demagogue.

-

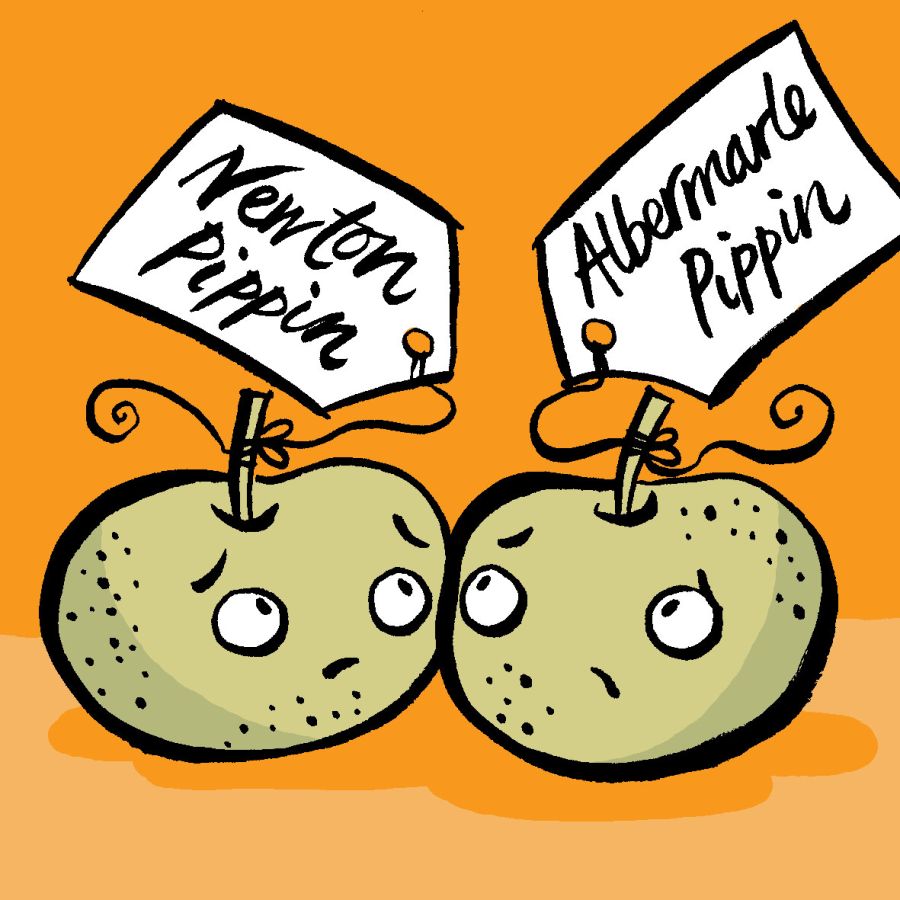

Other popular heirloom cider apples from New York State include Golden Russet and Jonathan, as well as the popular Newton or Albermarle Pippin (depending on whom and where you ask). A New York native, this apple was a favourite of Founding Fathers, including Benjamin Franklin, who first brought them to the UK, George Washington, and Thomas Jefferson, who complained that France had no apple as tasty during his tenure as ambassador. Grown at Mount Vernon and Monticello, the Pippin acclimated so well to Virginian soil that it was renamed locally as the Albermarle Pippin, for Virginia’s Albermarle County. Don’t ask for Newton Pippin cider in Virginia – ever.

Suitable for storage, which allows its initial tartness to mellow into notes of tangerine and pineapple, the Pippin (Albermarle in this instance) shot to fame when gifted to Queen Victoria by American minister Andrew Stevenson in 1838. Bringing apples from his wife’s Albermarle orchard, Stevenson succeeded in convincing Parliament to lift tariffs on this sought-after variety, an exemption that lasted until WWII. Like the Northern Spy, this apple is now cultivated for cider across the US. Just make sure you use the correct name.

-

Virginia

The home of Southern apples, Virginia’s cider culture is deeply rooted and its range of apples and flavours broad-reaching. In his recent book Virgina Cider, author and cider expert Alistair Reece highlights the difference in terroir-based properties of heirloom apples grown at different temperatures and elevations from the brisk peaks of the Piedmont to the warm valleys of the South. It’s impossible to write about Virginia heirloom apples without mentioning the Founding Fathers, Jefferson in particular, and his fingerprint is all over Virginia’s two best known native cider apples – the Virginia Hewe’s Crab and the Taliaferro (pronounced Toliver) – long thought to be extinct but now teetering precipitously on the brink of exciting rediscovery.

The Virginia Hewe’s Crab is a crossbreed of an indigenous American crab apple and domesticated European variety and was used in cidermaking from the early 1700s. Known for its pungent, intense banana-butterscotch flavour with notes of cinnamon, the Virginia Hewe’s Crab was so highly regarded that Jefferson devoted a significant portion of his north orchard to its cultivation and once wrote that crushing the juicy Hewe's Crab for cider was like "squeezing a wet sponge." Still hugely popular with cidermakers both in and outside of Virginia, this hardy apple was also used as a root stock and polliniser for other varieties, including Winesap, Black Twig and Arkansas Black, aiding its survival through heirloom apples’ lean years.

-

The Taliaferro is often known as the ‘holy grail’ of American heirloom apples. Reportedly Jefferson’s favourite variety (I know – when did he find time to govern between drinking all this cider?), the Taliaferro has been believed lost for several centuries now despite its early popularity. Among the prolific praise Jefferson heaped on Talliaferro cider, he named it “unquestionably the finest cyder we have ever known, and more like wine than any liquor I have ever tasted which was not wine” and “more body, is less acid, and comes nearer to the silky Champaigne than any other.” The country was definitely running itself.

Among apple detectives, the hunt for the elusive Taliaferro really has made it into the Moby Dick of apples. Back in 1994, the late ‘Professor Apple’ Tom Burford believed he had found it on the farm of a Mr. Conley Colaw in Highland County, Virginia, praising Colaw’s cider as “the richest, fullest-bodied farm cider I’d ever tasted.” Burford and other apple detectives have come up with numerous potential Taliaferros over the years, but their provenance has been unproven – until now. Washington State University’s Professor Cameron Peace is currently testing a Virginia-based heirloom apple tree which could herald a reappearance of this white whale. “We’ve tested a couple of trees of it, and the results show it to be genetically unique (i.e., not the same as something already under a different name) and with a pedigree position consistent with what we might expect from the true cultivar’s history,” Peace explains. “Both of those genotypic details keep it in the running of being the true Taliaferro.” While testing remains ongoing, American apple detectives are holding their collective breath in anticipation of the rediscovery of this Virginia legend.

-

New England

Beyond New York State, leafy New England has also proven a fertile habitat for heirloom apples since the early days of colonisation, with Vermont, Massachusetts, Connecticut, Rhode Island New Jersey and Maine all homes to cider apples of historic significance. The Rhode Island Greening, a tart, acidic apple with similar characteristics to a Granny Smith, is argued by some to be the oldest heirloom American cider apple. Also used in pie recipes including Martha Stewart’s (yes, her again), its tangy astringency has ensured its popularity among cidermakers across the US, but this is where the consistency ends, as numerous myths about its origins abound – some more deliciously fanciful than others.

-

Wikipedia will have you believe that the apple was discovered in the 1650s by one Mr Green in Green’s End, Rhode Island. Said Mr Green, a tavern keeper, shared scions with his patrons, spreading the apple across the colony and bestowing it with the name of ‘Green’s Inn, Rhode Island.’ Another more juicy tale involves one Metcalf Bowler a wealthy colonist and Revolutionary War spy who also owned a fleet of ships. Legend has it that when one of Bowler’s ships survived a brutal storm, they rescued the crew and passengers of a less fortunate vessel. One of these passengers was none other than the son of the Shah of Persia. And it gets better. As a gift of gratitude, the captain was given a sapling said to be grafted from the very tree whose apples seduced Eve and gave knowledge to humans. And we’re not done yet – an angel then visited Bowler in a dream, instructing him to plant the sapling outdoors, not in his greenhouse, because it needed conditions as optimal to the Garden of Eden as possible to thrive. While the veracity of this tale is highly unlikely, particularly as Bowler wasn’t even born until 1726, what could still potentially have some merit is the part where he served George Washington and the Marquis de Lafayette Rhode Island Greening cider (which he apparently named Eden’s Champagne) next to actual French champagne and both preferred the native cider. As far as I’m aware, Jefferson wasn’t there to exert an opinion.

-

New Jersey’s Harrison is a current darling of the craft cider world, it’s bright citrus-mineral flavours making a delectable single varietal, but it was very nearly lost forever. Originating in Newark around 1713 and named for businessman Samuel Harrison who discovered and cultivated it, the Harrison quickly became a cider superstar. Another favourite of Washington’s (fuel for battle I’m sure), it was advertised in the New York Post in the early 19th century, being consumed nationwide by the mid-late 1800s and even shipped to the Caribbean. As cider lost popularity and fell into decline as discussed in Part 1, the Harrison too seemed to fall into demise. However, a stroke of luck and some (literal) hard grafting saved it from the fate of so many of its fellows.

Vermont orchardist and apple detective Paul Gidez rediscovered the Harrison in 1976, having read about it in William Coxe’s 1817 A View of Cultivation of Fruit Trees, and the Management of Orchards and Cider, the first book to catalogue American fruit trees after the Revolution. Gidez saved the Harrison from certain disappearance when he managed to clip a cutting from a rare specimen just days before the tree was felled. Gidez shared his scions with Tom Burford, and the two worked diligently to revive the Harrison. As Harrisons take between four and twelve years to produce, they are still relatively rare and are saved primarily for the single-varietal production which allows their flavour – described by Coxe as “quince-like” and Burford as “rich and sprightly with a dry aftertaste” – to shine.

-

Craft cideries

Of course, this is the tip of the iceberg. All the US apple-producing regions have their own stories to tell, from North Carolina’s Kittageskee, rediscovered by Dave Benscoter, to Georgia’s Shockley, Kentucky’s Ben Davis to the Colorado Orange. And it’s not just in rural areas that heirloom apples are making a splash.

As demand for these palate-pleasing flavours takes off, craft cideries can be found everywhere in the US, with urban cideries on the rise. While not all are able to source their apples locally (those wiley hyperlocal survivors may not be strong enough in numbers and there may be a shortage of local orchards and cultivators), but even if they are bringing in juice from a more populous region, expect cidermakers to be putting their own spin on their product, building an audience and enjoying their craft. Urban cideries are a great resource for American cider lovers who may not live near major farm or orchard areas, and the likes of Phoenix AZ’s CiderCorps, Houston TX's City Orchard, St Petersburg FL’s Green Bench, Austin TX’s Texas Keeper, and North Carolina’s Botanist & Barrel are bringing top quality ciders made with heirloom apples to the heart of key craft beverage cities.

-

Demand from urban cideries is also fantastic for stimulating heirloom apple cultivation, cementing their importance in the craft cider movement and encouraging orchardists to allocate more space to heirloom trees. As we discovered in parts one and two, heirloom trees still make up a tiny fraction of apples grown in the US, so developing the market across the US is great for both producers and drinkers.

“As more and more of us pop up in non-traditional areas of the country, it has two effects: First, the demand for cider fruit goes up even faster than it already is,” explains Green Bench’s Head Cidermaker Brian Wing. “We need to create a situation where growing cider fruit makes good business sense for the farmers out there. Second, I hope urban cideries can help better influence perception of what cider can be for people who do not live in the traditional cider regions. That will expand the palates of cider drinkers and may even increase tolerance for the premium pricing that these products demand.”

-

Future of heirloom apples

For modern cidermakers, the possibilities offered by American heirloom apples really are endless, and paired with techniques such as wild fermentation, keeving and Method Traditionalle, the American cider scene is bubbling over with delicious, exciting offerings from around the country. The histories and mysteries around these apples add spice and intrigue on par with the tastiness of the ciders themselves, and there couldn’t be a better time to explore the world of American craft heirloom apple cider.

Andy Hannas, Head Cidermaker at Potter’s Craft Cider in Charlottesville, Virginia, highlights the importance of heirloom apples across the industry and what they offer for the future of craft cider in America. “Heirloom varieties have done a lot for the marketing and storytelling about the legacy of cider in the US which is great for the industry overall,” he says. “Most of the domestic growth in the cider category is coming from people making purchases at grocery stores. While those ciders might seem worlds away from those produced on small family owned orchards in rural areas, they are all drawing on the same legacy of American cider traditions. Just like every tiny craft brewer is part of the same legacy as Coors or Busch.” A perfect analogy to finish on.

-

Some key events in the US cider calendar include (but are not limited to) the American Cider Association’s annual CiderCon, Cider Week New York, Chicago Cider Week, the University of Idaho’s Heritage Orchard Conference, Scott Farm Orchard’s Heirloom Apple Day, and CiderFeast. Of course, while festivals are a really handy and convenient way to discover a lot of new ciders in one place, nothing quite beats the experience of an on-site visit, and with cider trails in all the major producing regions (including multiple in New York State), it’s easy to explore some really spectacular taprooms and ciders. Advice and recommendations can be found from local cider organisations such as the New York Cider Association, the American Cider Organisation and publications such as Cider Review, Cider Craft and Malus.

-

Further reading:

Lee Calhoun – Old Southern Apples

Darlene Hayes – Apple Tales

Jude & Adalyn Schuenemeyer - Colorado’s Fruit Growing History: Historic Context of Orchards

Helen Humphreys - The Ghost Orchard

John Bunker - Apples and the Art of Detection: Tracking Down, Identifying and Preserving Rare Apples

Alistair Reece & J. Mark Stewart - Virginia Cider: A Scrumptious History