Government and Hospitality – The Smoking Ban

Series: Regulatory HistoryTake a dive into modern history, 2007. It's the year the first iphone was released, it's when the final installment in the Harry Potter series was published, but most importantly for pubs it was the year the Smoking Ban was introduced.

Steve Dunkley takes you through what led to it and what was its impact.

Illustrations by Christine Jopling

- Pub Grub and Back Info

- The Children’s Certificate

- Grey Area

- The Smoking Ban

- Beer Gardens

- The Outcome

-

Arguably the most hotly contested government interference in the hospitality trade in recent years was the smoking ban of 2007. Even now, seventeen years later, people are still arguing about whether or not it was a good thing, and whether it was a step too far for the government to impose its views. Unlike previous government legislation this wasn’t a tax, but was seen as an attack on personal liberties.

-

Pub Grub and Back Info

Like many major overhauls in government policy, the roots of the smoking ban came earlier.

With the enactment of the Beer Orders eighteen years earlier, in 1989, a change in pub culture was set in motion. A lot of pubs came to the market, presenting the opportunity for an overhaul in pub ownership. Some of the first to take advantage of this were Michael Belben and David Eyre who, unable to afford to open a restaurant bought The Eagle in Farringdon in late 1989 and in early 1990 opened what became the first Gastropub. Pub food suddenly became a thing again, and aided by the widespread availability of commercial microwave ovens in the mid to late 80s, pubs up and down the country could look at providing reasonably priced, large portioned meals.

Five years later in 1994 the Deregulation and Contracting Out Act was put into law. Parts of this Act set out to change the Licensing Act of 1964, itself an attempt to consolidate various other Acts relating to the sale of alcohol, including a relaxation of when alcohol could be sold. But the main part that affected pubs was an addition to section 168, making it no longer an offence for people under the age of 14 to be present in a licensed premises, but with some caveats. There were three conditions: that the person under 14 had to be with someone aged 18 or over, that at least one member of the group had to be consuming a meal and that the bar had to have a Children’s Certificate associated with its premises

-

The Children’s Certificate

The Children’s Certificate was seen as the Government’s first attempt in recent times to clean up the image of the pub. The problem was, it seemed that the Government didn’t really know what pubs were outside of the outdated image of smoke filled dens of drunken iniquity; far removed from the private members clubs that were often frequented by the Members of Parliament. To allow for this general lack of understanding, the Act was worded in such a way to allow the local licensing justices leeway in what needed to be done:

Licensing justices may grant an application for a certificate under subsection (1) of this section (“a children’s certificate”) if it appears to them to be appropriate to do so, but shall not do so unless they are satisfied —

(a) that the area to which the application relates constitutes an environment in which it is suitable for persons under fourteen to be present, and

(b) that meals and beverages other than intoxicating liquor will be available for sale for consumption in that area.

According to the letter of the law, meals had to be available, that one person in the group was having a meal, and that the environment was suitable for someone under 14. The last part being a very grey area.

-

Grey Area

As Gastropubs took off across the country they contributed to the desire for families to take their children with them when going out to the pub, and the pubs that had taken advantage of the trend for food were also quick to take advantage of the Children’s Certificate, removing a couple of tables to define a separate area and even building partition walls if needed.

With there being no national stipulation of what constituted a suitable environment, local variations were rife, and some of the requirements were seen as a bit heavy handed.

Whilst some licensing justices agreed that installing ventilation equipment throughout an entire open plan pub was a bit overboard, others determined it a necessity. Some said that fruit machines could be in the pub, just not near the area that children were allowed. Others went a bit further and said that any fruit machine had to have the sounds turned off. Other justices went further still and ruled that there could be no fruit machines at all.

-

What constituted a “meal” wasn’t the contentious issue that it was during the easing of the Covid restriction, bar snacks were seen as just that, snacks – things to keep you going until you had a meal, and going out to eat usually meant a restaurant. The sandwich and snack culture hadn’t taken root then and the wording of the Act itself didn’t mention “substantial”, just “meal”.

Some pubs were lucky to have separate rooms and for them getting a Children’s Certificate was easier, although applications for them did still meet some objections from local justices, and residents who feared that children would be abandoned in one area of the pub while their parents socialised in the bar over a pint and a cigarette. And there were the inevitable objections from the male dominated regulars to having families and children in their sanctuaries.

-

The Smoking Ban

By the time of the introduction of the smoking ban in 2007 the UK pub culture had already changed.

The Health Act 2006 didn’t just cover pubs, but all enclosed public places as well as workplaces, work vehicles, hire cars and public transport. Anywhere where second hand smoke could be an issue was affected.

But for pubs in particular, it hit hard. Even though they knew it was coming.

What was actually coming though, kept changing. Initially it was only going to be for pubs that sold food or allowed children – those that had taken advantage of the growing trend for food or had gone for the Children’s Licence.

As with the beer ties, what was actually introduced as law wasn’t what was originally suggested. But whereas the beer ties were watered down, the smoking ban was strengthened.

Initially the smoking ban was to be phased in, starting with hospitals, doctors surgeries and other NHS buildings in 2006 followed by public buildings in 2007, and then restaurants and pubs that sold food in 2008.

This partial ban on pubs didn’t sit well though with all those pub chains that had gone down the route of serving food or got their Children’s Licence. The thought that they would have to ban smoking completely, but those pubs only serving bar snacks to adults could continue to allow smoking was a step too far and they lobbied their local MPs, as well as the Government in general. Over 90 MPs signed a motion backing the call for a total ban in pubs.

-

On the morning of Sunday 1st July 2007 there was no longer any smoking in enclosed public spaces, and the pubs stank. They absolutely reeked.

Some pubs decided to close for the day and to refurbish. They ripped out and replaced the carpets and upholstered seating, they repainted all the walls. The smell of fresh paint overpowered everything but the stale urine in the gents.

Other pubs went down the cleaning route, deep cleaning all the soft furnishings, the floors and walls, and leaving the bars smelling heavily of chemicals. Other pubs still just opened their doors with the aroma of stale tobacco the last reminder of what their customers were now missing. Nowhere was pleasant to walk into that day. And being able to suddenly see everything clearly without the smoky haze, with clean lamp shades and new light bulbs, highlighted the deterioration that pubs had been left to.

-

Beer Gardens

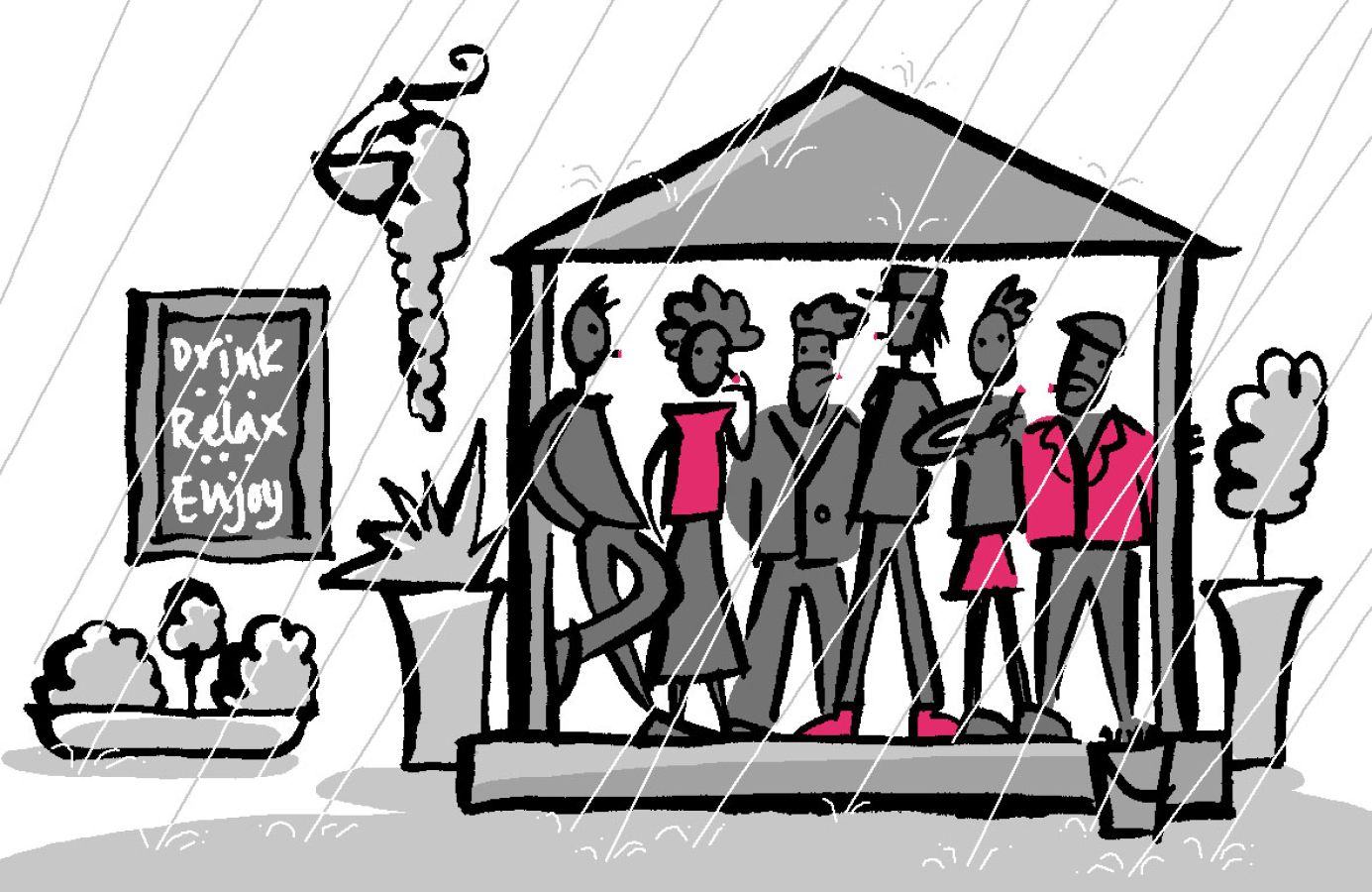

All of these renovations, upgrades and cleaning cost pubs money, but it was money they had to spend if they wanted to keep trading in the hope that they wouldn’t lose custom. But over the next few weeks things changed. Walking along the streets, pubs seemed busier than ever before, every entrance was thronged with what appeared to be overspill from inside, groups hanging around drinking in the street. But when you went inside you realised that almost the entirety of a much reduced customer base were standing outside, having a cigarette. Beer gardens became smoking gardens and publicans became innovative in outside smoking shelters, laying down the groundwork for what would, 13 years later be used for outside drinking areas during the Covid restrictions.

-

The Outcome

Seventeen years since smoking was banned in pubs, the general clientele has changed – pubs are no longer the refuge of men drinking pints, but they've adapted. Food is commonplace, children are often welcome, women are rarely stared at as oddities.

What’s worth noting about the smoking ban is that the rate of decline in the number of smokers didn’t increase. In fact for the first three years after the ban was introduced the number of smokers remained roughly the same, and when the decline started again it was at a slower rate than before. So it could be seen that, if anything, the smoking ban had the opposite effect than was hoped for, and that is what is argued when people still oppose it.

But what has drastically fallen is the amount of passive smoking. What is often overlooked or forgotten is that the smoking ban itself wasn’t about stopping individuals from smoking, but from harming others in their vicinity. So it is arguable that it was a case of the Government interfering with the civil liberties of the few, but rather that it was a case of protecting the many – at the expense of the pub culture.